In aqueous solutions, reactions typically involve substances dissolved in water, where water serves as the solvent. The substances dissolved are called solutes, and they can be ionic or molecular compounds. Here are the common types of reactions that occur in aqueous solutions:

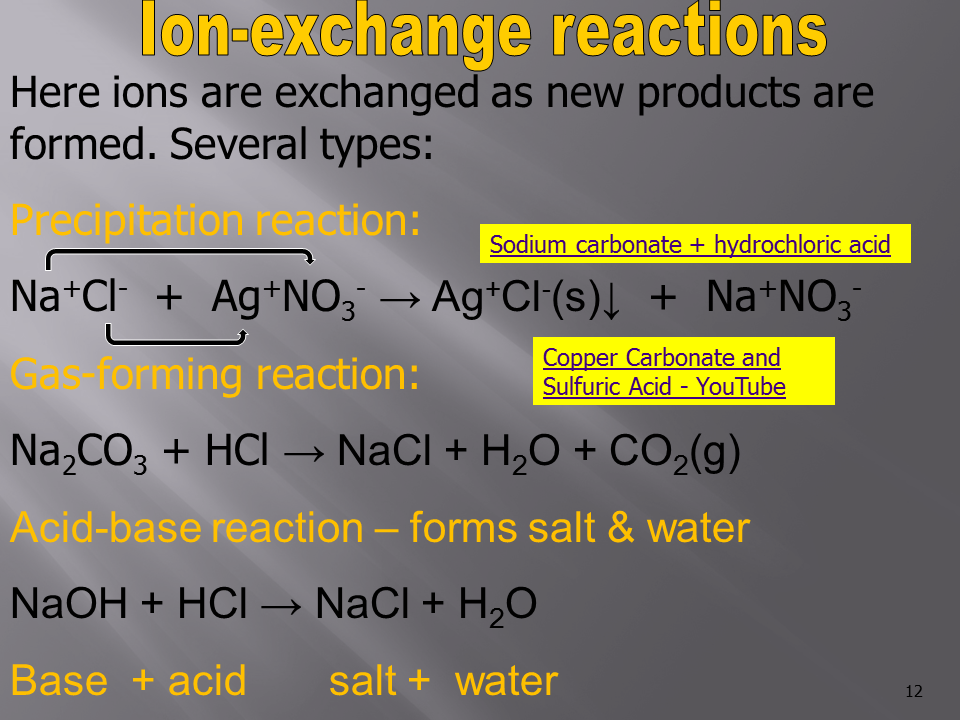

1. Precipitation Reactions

- These occur when two aqueous solutions are mixed, and an insoluble solid (precipitate) forms.

- Example: Mixing silver nitrate (AgNO₃) and sodium chloride (NaCl) solutions forms a precipitate of silver chloride (AgCl).

- Reaction:

[AgNO₃(aq) + NaCl(aq) \rightarrow AgCl(s) + NaNO₃(aq)]

2. Acid-Base Reactions (Neutralization Reactions)

- An acid reacts with a base to form water and a salt.

- Example: Hydrochloric acid (HCl) reacts with sodium hydroxide (NaOH).

- Reaction:

[HCl(aq) + NaOH(aq) \rightarrow NaCl(aq) + H₂O(l)]

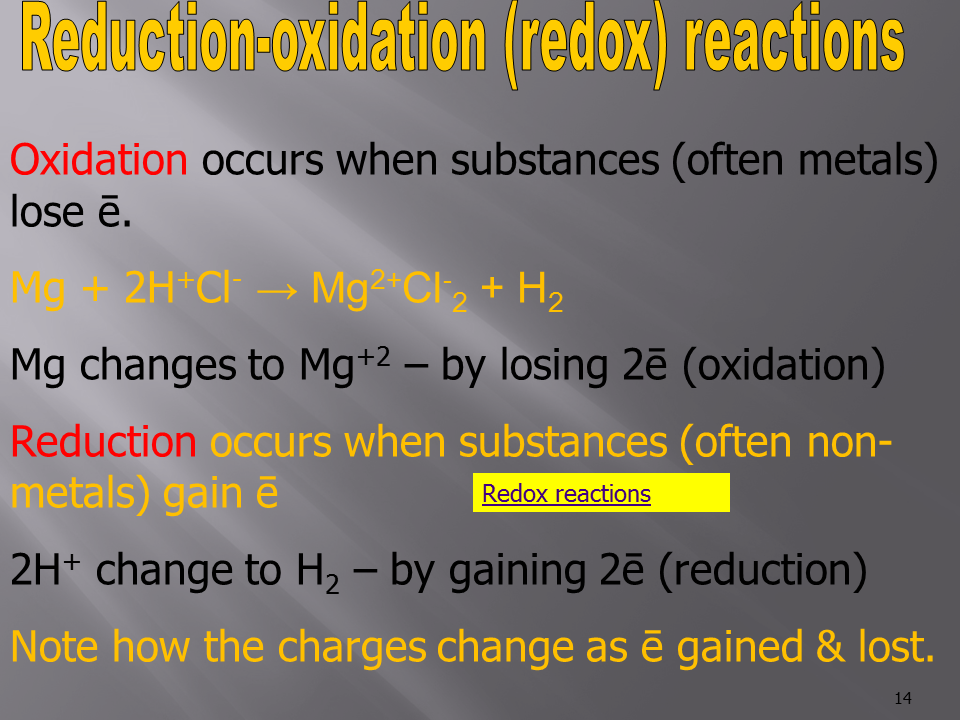

3. Oxidation-Reduction (Redox) Reactions

- In these reactions, one substance loses electrons (oxidation), and another gains electrons (reduction).

- Example: Zinc metal reacts with copper(II) sulfate (CuSO₄) in an aqueous solution.

- Reaction:

[Zn(s) + CuSO₄(aq) \rightarrow ZnSO₄(aq) + Cu(s)]

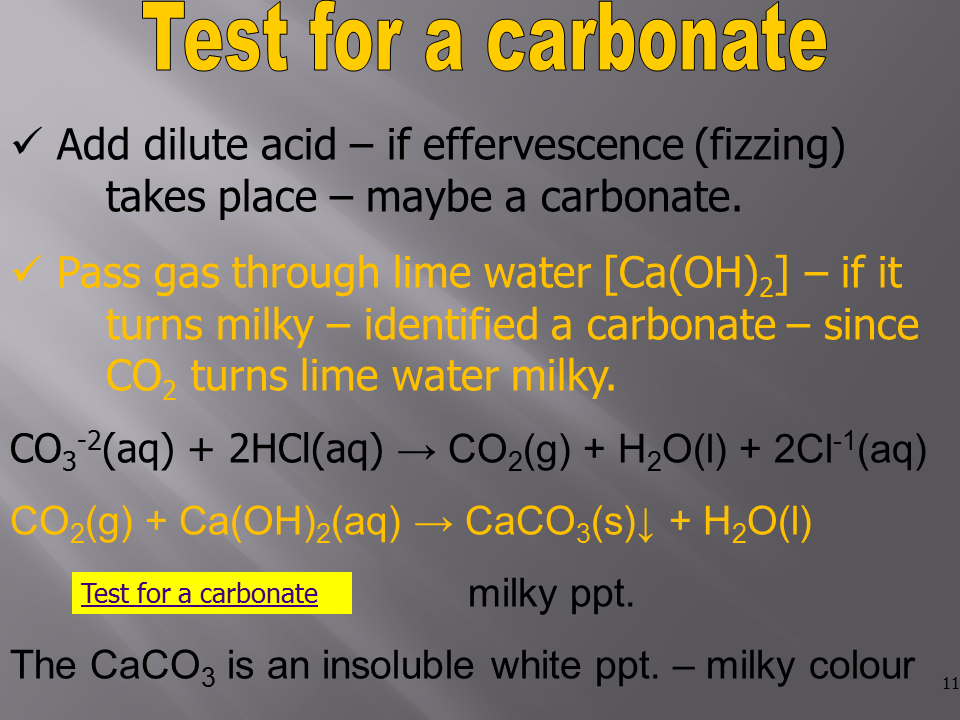

4. Gas Formation Reactions

- Some reactions in aqueous solutions produce a gas as a product.

- Example: Reaction between hydrochloric acid and sodium carbonate produces carbon dioxide gas.

- Reaction:

[2HCl(aq) + Na₂CO₃(aq) \rightarrow 2NaCl(aq) + CO₂(g) + H₂O(l)]

5. Double Displacement Reactions

- Two compounds exchange ions, resulting in the formation of two new compounds.

- Example: Potassium iodide (KI) reacts with lead(II) nitrate (Pb(NO₃)₂), forming lead(II) iodide (PbI₂) as a precipitate.

- Reaction:

[2KI(aq) + Pb(NO₃)₂(aq) \rightarrow PbI₂(s) + 2KNO₃(aq)]

Characteristics of Aqueous Reactions:

- Electrolytes: Substances that dissolve in water to form ions (e.g., NaCl → Na⁺ + Cl⁻).

- Nonelectrolytes: Substances that dissolve in water but do not produce ions (e.g., sugar).

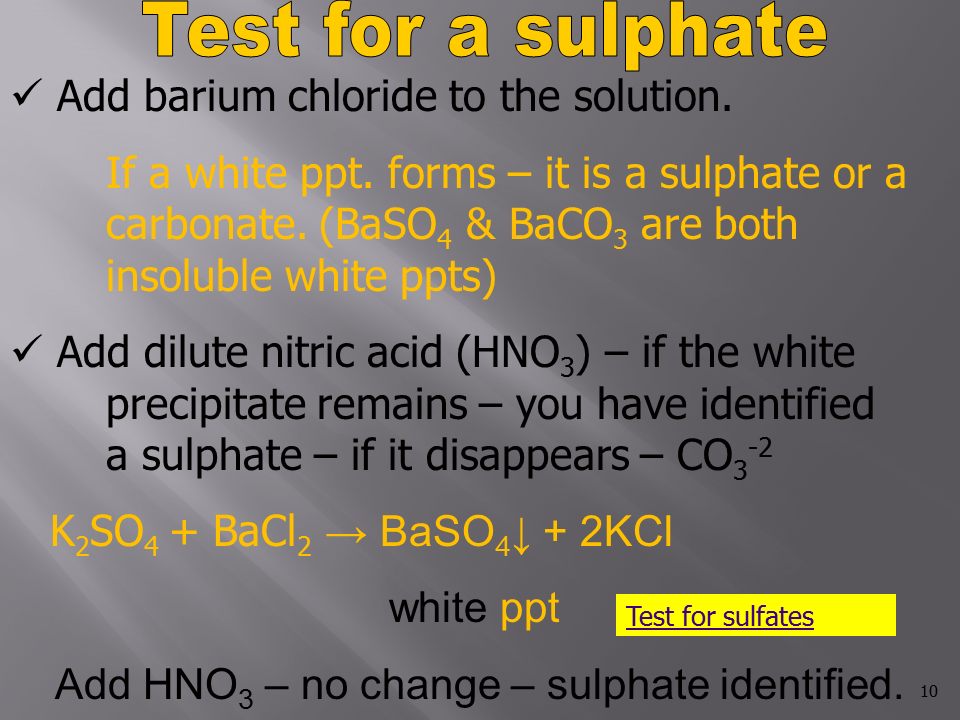

- Solubility: Precipitation reactions depend on the solubility rules, which dictate whether a compound will dissolve or form a precipitate.

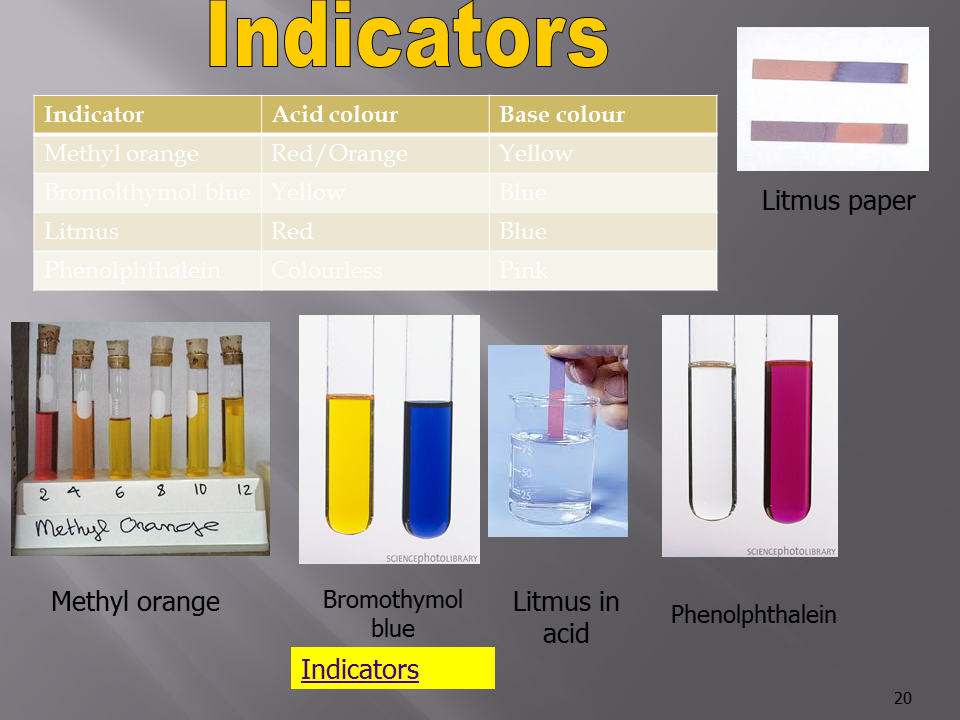

Common Indicators of Aqueous Reactions:

- Formation of a precipitate.

- Change in color.

- Formation of a gas (bubbling).

- Release or absorption of heat (temperature change).

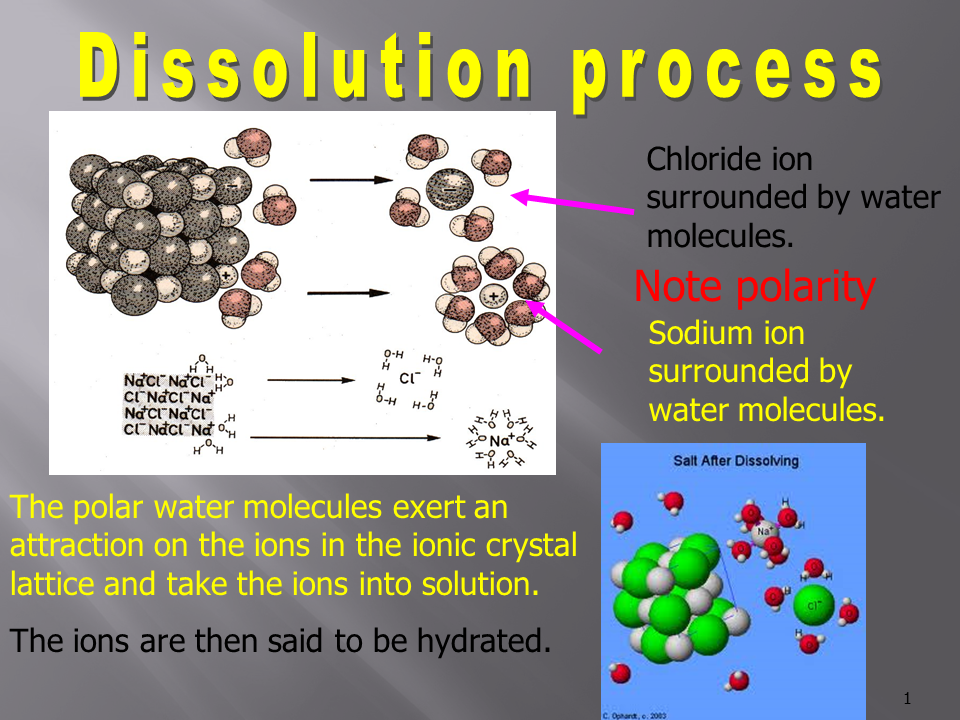

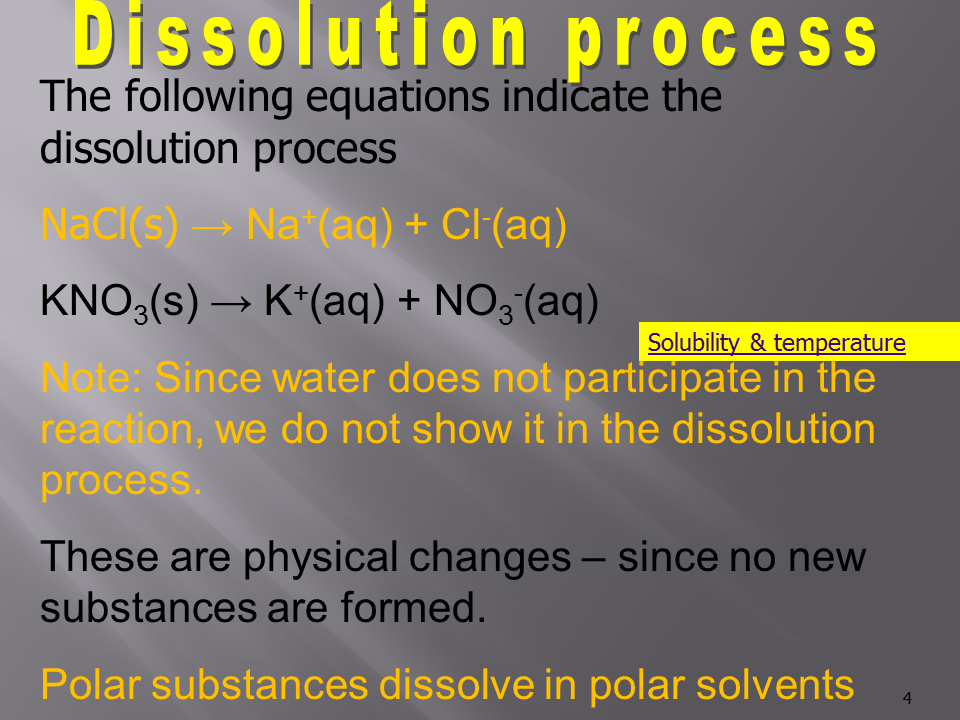

The dissolution process involves the interaction between a solute and a solvent, resulting in the formation of a homogeneous solution. In an aqueous solution, water acts as the solvent. The process can be broken down into the following key steps:

1. Breaking Solute-Solute Interactions

- If the solute is ionic (e.g., NaCl) or molecular (e.g., sugar), the first step is to break the bonds or interactions between solute particles (e.g., ions or molecules).

- Energy is required to overcome the forces holding the solute particles together. For instance, in the case of NaCl, the ionic bonds between Na⁺ and Cl⁻ must be broken. [NaCl(s) \rightarrow Na⁺(aq) + Cl⁻(aq)]

2. Breaking Solvent-Solvent Interactions

- Water molecules (the solvent) are held together by hydrogen bonds. For solvation to occur, some of these water-water interactions must be disrupted to create space for the solute particles.

- This step also requires energy.

3. Solvation (Hydration in Water)

- Once the solute particles are separated, they become surrounded by solvent molecules. In the case of an aqueous solution, this process is called hydration.

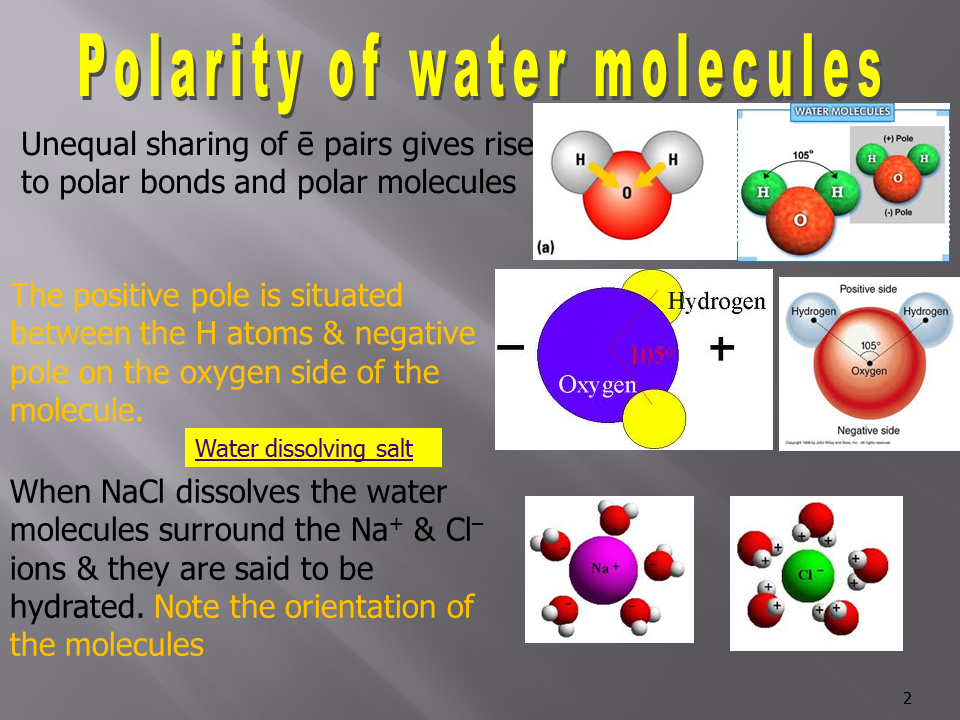

- Water molecules are polar, with the oxygen atom carrying a partial negative charge and the hydrogen atoms carrying partial positive charges. As a result, water molecules align themselves around ions or polar molecules.

- For cations (positively charged ions), the oxygen ends of water molecules (negative dipoles) face the ion.

- For anions (negatively charged ions), the hydrogen ends of water molecules (positive dipoles) face the ion.

- During this step, energy is released because of the attractive forces between the solute particles and the solvent molecules. Example: Hydration of Sodium Chloride (NaCl):

- The Na⁺ ion is surrounded by the oxygen ends of water molecules.

- The Cl⁻ ion is surrounded by the hydrogen ends of water molecules.

4. Equilibrium

- In some cases, dissolution leads to an equilibrium between dissolved solute and undissolved solute, especially in saturated solutions. Once the solution reaches saturation, no more solute can dissolve, and any additional solute will remain undissolved.

Factors Affecting the Dissolution Process:

- Nature of the Solute and Solvent:

- Like dissolves like: Polar solutes dissolve in polar solvents, and nonpolar solutes dissolve in nonpolar solvents.

- Ionic and polar substances dissolve well in water because of water’s polar nature.

- Temperature:

- For most solids, increasing the temperature increases solubility, as more energy is available to break the solute-solute interactions.

- For gases, increasing temperature usually decreases solubility.

- Pressure (for Gases):

- An increase in pressure increases the solubility of gases in liquids (described by Henry’s law).

- Agitation (Stirring):

- Stirring increases the contact between solute and solvent, speeding up the dissolution process.

- Surface Area of the Solute:

- The greater the surface area of the solute (e.g., finely powdered vs. large chunks), the faster it will dissolve, as more solute particles are exposed to the solvent.

Example: Dissolution of Sugar (Sucrose) in Water

When sugar (a polar molecule) dissolves in water, hydrogen bonds between the sugar molecules and the water molecules form, allowing sugar to spread evenly throughout the water.

[C_{12}H_{22}O_{11}(s) \rightarrow C_{12}H_{22}O_{11}(aq)]